عاجل:

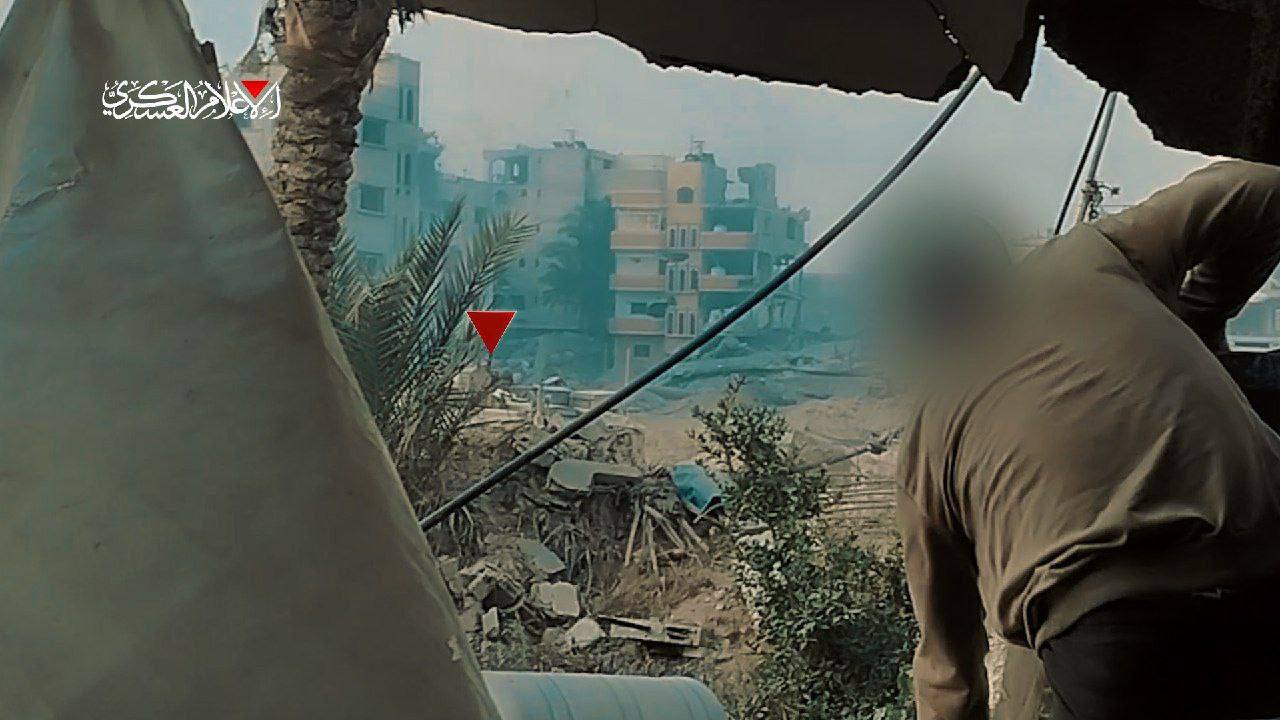

وزارة الخارجية: الهدف من الحظر هو الضغط على الكيان الصهيوني لإنهاء العدوان ورفع الحصار عن غزة ودخول المساعدات

وزارة الخارجية: حظر الملاحة الصهيونية جاء بعد عجز المجتمع الدولي والأمم المتحدة عن إيقاف العدوان وفك الحصار عن غزة منذ ما يزيد عن 21 شهرا

وزارة الخارجية: نجدد حرصنا على حرية وسلامة الملاحة في البحر الأحمر وأن حظر الملاحة البحرية يقتصر على الكيان الصهيوني فقط

وزارة الخارجية: المبعوث الأممي يلوذ بالصمت عندما يُقدم الكيان الصهيوني على استهداف المدنيين والأعيان المدنية في اليمن

وزارة الخارجية: كان يفترض أن يُعرب المبعوث عن القلق من العدوان الصهيوني المستمر على اليمن والذي يستهدف أعيانا مدنية

وزارة الخارجية: بيان المبعوث الأممي إلى اليمن يفتقر إلى التوازن والحياد

وزارة الخارجية: بيان المبعوث الأممي تجاهل جرائم الإبادة الجماعية التي يرتكبها الكيان الصهيوني في غزة أمام مرأى ومسمع من الأمم المتحدة

وزارة الخارجية: البيان يعكس عدم حيادية المبعوث الأممي الذي تجاهل بشكل كامل الأسباب الجذرية للتصعيد في البحر الأحمر

وزارة الخارجية والمغتربين: نندد بانحياز المبعوث الخاص للأمين العام للأمم المتحدة إلى اليمن في البيان المنسوب إليه بشأن الوضع في البحر الأحمر

السيد القائد: خاتمة استجابة شعبنا لله سبحانه وتعالى هي ما وعد الله به عباده المتقين من النصر والفتح المبين