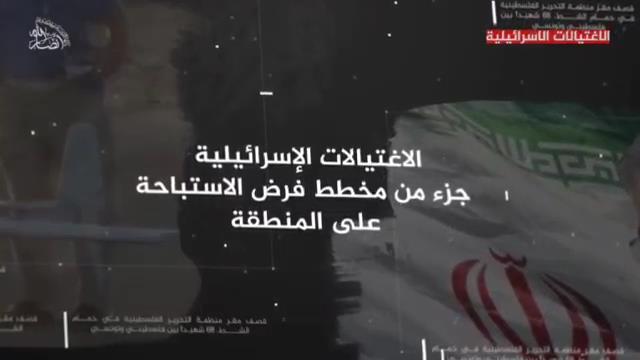

ناطق حكومة التغيير والبناء: الغارات لن تثني شعبنا عن دعم غزة، واليمن سيدافع عن نفسه وأرضه ومقدراته ويردع العدوان

ناطق حكومة التغيير والبناء: تكرار استهداف موانئ سبق وأعلن العدو مراراً بأنه دمرها بالكامل، دليل كافٍ بأن الشعب اليمني لا يقهر

ناطق حكومة التغيير والبناء: الرد اليمني قادم وقريب بإذن الله وعلى العدو ترقب ذلك

ناطق حكومة التغيير والبناء: العدو الصهيوني وشريكه الأمريكي يتحملان كامل المسؤولية عن تداعيات العدوان على ميناء الحديدة

المنظمة الدولية للهجرة: مقتل ما لا يقل عن 50 شخصًا بعد اندلاع حريق في سفينة تقل 75 لاجئًا سودانيًا قبالة سواحل ليبيا

القوات المسلحة اليمنية: مستمرون في تأدية واجباتنا حتى وقف العدوان على غزة ورفع الحصار عنها

القوات المسلحة اليمنية: العدوان الإجرامي سيصل إلى مختلف البلدان ما لم تتحرك الشعوب وتتحرك الدول للصمود والمواجهة

القوات المسلحة اليمنية: نجدد الدعوة لأبناء أمتنا بتحمل مسؤوليتهم تجاه إخواننا في غزة الذين يتعرضون للإبادة والتجويع والتهجير

غزة: طيران العدو يقصف الطابق العلوي لمستشفى الرنتيسي للأطفال غرب مدينة غزة

بيان مهم للقوات المسلحة اليمنية في تمام الساعة 9:10مساءً، بعد قليل.